Made possible by

Showing Up For Me and You

Mental Wellness Patch Program

for Seniors and Ambassadors

Facilitator Guide

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 2

Mental Health Disclaimer

The contents of the Mental Wellness Patch Program for

Seniors and Ambassadors: Showing Up For Me and You is

for informational purposes only. This program was made in

partnership with the HCA Healthcare Foundation and the

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). The information

presented by this program is not an attempt by Girl Scouts

of the USA (“GSUSA”) to practice medicine or to give specic

medical advice, including, without limitation, advice concerning

the topic of mental health. Therefore, the information from

this program should not replace consultation with your doctor

or other qualied mental health providers and/or specialists.

Never disregard, avoid, or delay obtaining advice from your

licensed mental health care provider because of something you

have read or experienced through our program. If you believe

you or another individual is suffering a mental health crisis or

other medical emergency, contact your doctor immediately, seek

medical attention immediately in an emergency room, or call 911

or 988 (the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline).

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America (GSUSA). All rights reserved. Not for commercial use. This material

is proprietary to GSUSA and may be used, reproduced, and distributed exclusively by GSUSA staff, councils, Girl Scout

volunteers, service units, and/or troops solely in connection with Girl Scouting.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 3

Table of Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4

Mental Wellness Tips for Facilitators ....................................................................................... 5

Planning and Preparation ...........................................................................................................7

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide ..................................................................................... 10

Next Steps ................................................................................................................................... 20

For Facilitators: Customizable Invitation Email

to Parents/Caregivers ...........................................................................................................21

For Facilitators: Customizable Post-Event Email to Parents/Caregivers ....................... 22

Meeting Aids .............................................................................................................................. 23

For Facilitators: Mental Health Terms to Know

For Facilitators: Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions

For Facilitators: What to Know About Identity, Culture, and Mental Health

For Facilitators: Girl Scout Safety Activity Checkpoints

—Overall Health, Well-Being, and Inclusivity

For Seniors and Ambassadors: Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions

For Seniors and Ambassadors: Your Language Matters

For Seniors and Ambassadors: Getting the Right Start

For Seniors and Ambassadors: How to Help a Friend

For Seniors and Ambassadors: Active Listening Checklist

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 4

Girl Scouts of the USA (GSUSA) has made a commitment

to support mental wellness for every Girl Scout because

we recognize that young people are currently facing a

mental health crisis. They are more likely than ever before

to attempt suicide, commit self-harm, and suffer from

depression and anxiety. And yet, people continue to be

uncomfortable discussing these issues. This discomfort

can be driven by the stigma often associated with mental

health issues. GSUSA wants to help start the conversation

and give Girl Scouts tools and support to better understand

and care for their mental health.

Mental health encompasses emotional and psychological

health—it impacts how we think, feel, and act. Everyone

has a state of mental health, just as everyone has a state

of physical health. Our mental health may include a

condition, such as depression or anorexia. Such a condition

can be permanent or temporary. It can be based on our

environment (such as attending online school due to the

COVID-19 pandemic) or on our response to life events.

It’s important to remember, though, that a person can

experience poor mental health without the diagnosis of a

mental health condition. Mental wellness refers to how we

take care of our mental health. It includes all the things we

might do to help realize our potential, cope with stress, and

productively contribute to our community.

What Is the “Showing Up For Me and You” Patch

Program for Seniors and Ambassadors?

GSUSA developed the Mental Wellness Patch Program

for Seniors and Ambassadors: Showing Up For Me

and You to equip high school Girl Scouts with tactics for

practicing self-care, coping with difcult situations, and

helping themselves and others. We show facilitators how

to deal with questions and concerns, and offer participants

the resources to explore, share, and reect from a space

where they can hang out and be themselves.

The Showing Up For Me and You Patch Program for Seniors

and Ambassadors was created in collaboration with experts

at the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the

nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization

dedicated to building better lives for the millions of

Americans affected by mental illness. We received

additional input from an advisory group made up of mental

health professionals and Girl Scout council leaders.

The Showing Up For Me and You Patch Program for

Seniors and Ambassadors was generously funded by the

HCA Healthcare Foundation, whose mission is to promote

health and well-being and make a positive impact in all

the communities served by HCA Healthcare, one of the

nation’s leading providers of healthcare services. Thanks to

HCA Healthcare Foundation’s support, GSUSA is working

toward the larger goals of destigmatizing mental illness,

normalizing conversations around mental health and

mental illness, and delivering inclusive programs for

Girl Scouts of all backgrounds.

Introduction

Mental Wellness—Why Now?

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 5

Mental Wellness Tips for Facilitators

Creating a supportive environment is especially important for a mental wellness program. Here are best practices

and tips to help make this a meaningful experience for everyone.

● Mental health can be a difcult topic to discuss with

young people. It’s impossible to know everything

about their lives and how certain topics in this Mental

Wellness Patch Program will affect them. Give them

permission to stop or skip an activity if they don’t

feel comfortable. This is where having more than one

volunteer will come in handy.

● When a topic comes up that you don’t feel equipped

to address, let Seniors and Ambassadors know you’re

putting it in the “parking lot.” This means you’ll be

parking the issue for now. Write it down so you can

follow up later. This gives you the time to get more

information if needed. Parking lots are also helpful if you

run out of time to discuss something. Write the topic on

a large piece of paper to revisit either later in the program

or at another meeting. Preparing yourself to come back

to parking lot items builds trust with the group.

● Let Seniors and Ambassadors know that

condentiality is key. However, if you hear or see

something you need to share about a Senior or

Ambassador, contact your council for guidance.

The meeting aid Girl Scout Safety Activity

Checkpoints—Overall Health, Well-Being, and

Inclusivity (p. 31) also provides guidelines for

addressing and reporting mental health concerns

about a Girl Scout.

● Tell participants they can share or not, depending on

how they feel. Everyone has different experiences,

comfort levels, and abilities to discuss a topic, and

there should be no pressure on anyone to share.

However, if you notice one or two participants doing

most of the talking, you can redirect the conversation

by saying:

• “Yes, I see where you’re going with that. I’d love to

hear thoughts from other people in the group.”

• “Let’s pause for just a moment to allow the entire

group to reect on or respond to what you said.”

• “Thanks for sharing! What do other people

think?”

● Encourage participants to speak up if they hear a

hurtful comment or would like to recognize and repair

something that may have hurt someone else. Even

when someone means well, they can still say things

that might negatively impact others. Taking a moment

to recognize when something we said has hurt

someone helps to strengthen our friendships.

The subjects of mental wellness and mental health can be delicate—

you’re not expected to be an expert or have all the answers.

Maintain a Girl Scout-led environment.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 6

● Use person-rst language. A person isn’t dened

by a condition and shouldn’t be addressed as such.

A person experiences bipolar disorder—they aren’t

bipolar. A person experiences mental illness—they

don’t belong to a group called “the mentally ill.”

● Be open to “checking” the group’s stigmatizing

language. Challenge misconceptions. If you hear

someone use harmful language, let them know. For

instance, words like “crazy” or “insane” reinforce the

idea that mental health conditions are extreme, rather

than the reality that they are quite common. Instead,

we should say things like, “someone with a mental

health condition” or “someone who has depression.”

● Don’t use mental health conditions as adjectives.

A person shouldn’t say they have “OCD” because they

like to organize or say the weather is “bipolar” because

it keeps changing. Doing this minimizes the actual

lived experiences of people who have mental health

conditions.

● Be cautious when talking about suicide. Suicide

is a sensitive topic and should be discussed in a way

that is respectful to the person and their loved ones.

A person is “lost to suicide” or “died by suicide” rather

than “committed suicide.” If a person tries to take their

life, they “attempted suicide” as opposed to “had an

unsuccessful suicide.” Make sure Girl Scouts aren’t

speaking about suicide in a casual way (i.e., “That test

was so hard, I wanted to kill myself”); suicidal ideation

shouldn’t be treated lightly.

● Avoid the terms “others” or “abnormal.” Referring

to people experiencing mental illness as “others” or

“abnormal” creates an “us versus them” narrative.

This can make people with mental illness seem inferior

and as though they’re the outliers of society—which

they aren’t.

● Avoid talking about or labeling feelings as good or

bad, positive or negative, normal or not normal.

Think of emotions as information we pay attention to

and learn from.

Finally, make sure to listen and reect. Reecting is an intentional, purposeful time to examine, ask questions,

and think about an activity or experience. After each section of the program, engage in reection. It helps

participants move forward with a deeper understanding of what they learned.

Help the group understand the importance of the language we use to

discuss mental health. Words are powerful; they can both heal and

harm. Using language that is respectful, accurate, and empathetic

helps to break the stigma related to mental health conditions.

Mental Wellness Tips for Facilitators

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 7

Planning and Preparation

Take these steps to plan and prepare. Remember, this program is designed for

Seniors and Ambassadors and not intended to be a multi-troop experience.

● Read through this guide to familiarize yourself

with the content, including facilitation tips and

suggestions, scripts and activity guides, and

meeting aids.

● Carefully review the following meeting aids for

facilitators:

• Mental Health Terms to Know and Symptoms

of Mental Health Conditions to learn the proper

vocabulary and denitions so you can use them

correctly and consistently.

• What to Know About Identity, Culture, and

Mental Health to understand how identity and

cultural background can affect responses to

mental health issues and access to treatment

in different communities. This information may

apply to participants.

• Girl Scout Safety Activity Checkpoints—

Overall Health, Well-Being, and Inclusivity

to see guidelines for addressing and reporting

mental health concerns about a Girl Scout.

Contact your council for additional guidance

or to obtain the full version of Safety

Activity Checkpoints.

• Your Language Matters: You’ll give this meeting

aid to participants during Activity 2 (p. 14), but

you can also keep a copy with you to reference as

needed. If anyone uses stigmatizing language at

any point, you can gently say: “Remember, saying

_______________ can be stigmatizing to people

with mental health conditions. Instead, let’s say

__________.”

● Take the “The Mental Wellness Patch Program:

Why It Matters and How to Implement It” course

in gsLearn (required):

• “The Mental Wellness Patch Program: Why It

Matters and How to Implement It” (approximately

20 minutes) allows you to learn more about

mental health conditions and how they affect

the group you’ll be working with. We never know

what others are going through, so being prepared

for sensitive topics and big emotions will help you

feel more condent in facilitating the Showing Up

For Me and You Patch Program for Seniors and

Ambassadors.

● Take two gsLearn courses that provide additional

support for leading the Showing Up For Me and

You Patch Program for Seniors and Ambassadors

(strongly encouraged):

• “GSUSA Mental Wellness 101” (approximately 35

minutes) offers a foundational understanding of

mental health and social-emotional development

stages, as well as tools to support the Girl Scouts

you work with. (Note, however, that it isn’t a

specic training for delivering the Showing Up

For Me and You Patch Program for Seniors and

Ambassadors.)

• “GSUSA Delivering Inclusive Program”

(approximately 20 minutes) lets you practice

using inclusive and equitable language to support

the identities of all Girl Scouts and foster a

cohesive environment.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 8

● Decide on a location and plan your setting. You can

hold the Showing Up For Me and You Patch Program

for Seniors and Ambassadors as an in-person troop

meeting or a council or service unit event.

For an in-person troop meeting:

• We recommend having a group of no more

than ten Seniors and Ambassadors.

• To accommodate a larger troop, you could

consider splitting into two groups, with at least

one facilitator overseeing each. Use additional

volunteers to help facilitate as needed.

• Create a relaxing space that’s quiet and cozy

for the group. Think about pillows or sitting on

a comfortable rug or chairs.

• Nature is nurturing. If possible, consider

meeting outdoors, somewhere quiet

and private.

For a council or service unit event:

• Reserve a location in advance.

• Send out information to participants at least

two weeks before with relevant information

about time, location, and parking. Send

reminders up to the day.

• At the event, divide Seniors and Ambassadors

into groups of no more than ten. Have at least

one facilitator for each group; use additional

facilitators as needed.

● Recruit mental wellness experts and other

volunteers to help facilitate.

• To the extent possible, bring in experts and

volunteers who reect the community of Girl

Scouts they’ll be supporting.

• Talk to your council and friends and family

network about relationships they might have

with mental wellness experts and professionals to

help with support. For example, reach out to your

local NAMI afliate to see if they can help you

nd volunteers. (Note: It may be best not to invite

a professional who provides services to one of the

Girl Scouts in your group, since that may impact

the participation of the Girl Scout and can lead to

a breach of condentiality.)

• Enlist other volunteers to help facilitate breakout

groups as needed.

● Reach out to participants and their families or

caregivers in advance.

• Send an invitation for Seniors and Ambassadors

to take part. (See the Customizable Invitation

Email to Parents/Caregivers meeting aid p. 21.)

• Assure them this will be a comfortable space for

participants to learn about mental wellness. It’s

possible that families may want to opt out, and

that’s okay, too.

• If you’re hosting Showing Up For Me and You

Patch Program for Seniors and Ambassadors is

in a different location than your regular troop

meetings, make sure to provide the address

and directions.

● Gather and print out activity materials and

meeting aids for Seniors and Ambassadors.

• Read through the materials list in the “Showing

Up For Me and You Patch Program for Seniors

and Ambassadors at a Glance” chart on page 9 to

know what specic items you’ll need and what to

prepare ahead.

• View NAMI’s short video Ending the Silence

before showing it to the group, so you’re prepared

to lead the discussion during Activity 1 (p. 12). It

goes over the ten most common signs of a mental

health condition.

● Be prepared to accommodate the age differences

or maturity levels in your group. Experience and

maturity levels can vary among 9th to 12th graders

(14- to 18-year-olds). You know your group best.

Read through the activities and decide if you want

to separate participants into smaller teams by age.

Keep in mind, though, that it can be valuable to

group younger participants with older ones to share

experiences.

• Think about what you are personally willing

to share. Participants might not always be

comfortable initiating or contributing to the

conversation. Hearing from you could give them

more condence to share their own experiences.

For example, you might say, “I was really sad

when I found out that my best friend was moving

to another state.”

Planning and Preparation

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 9

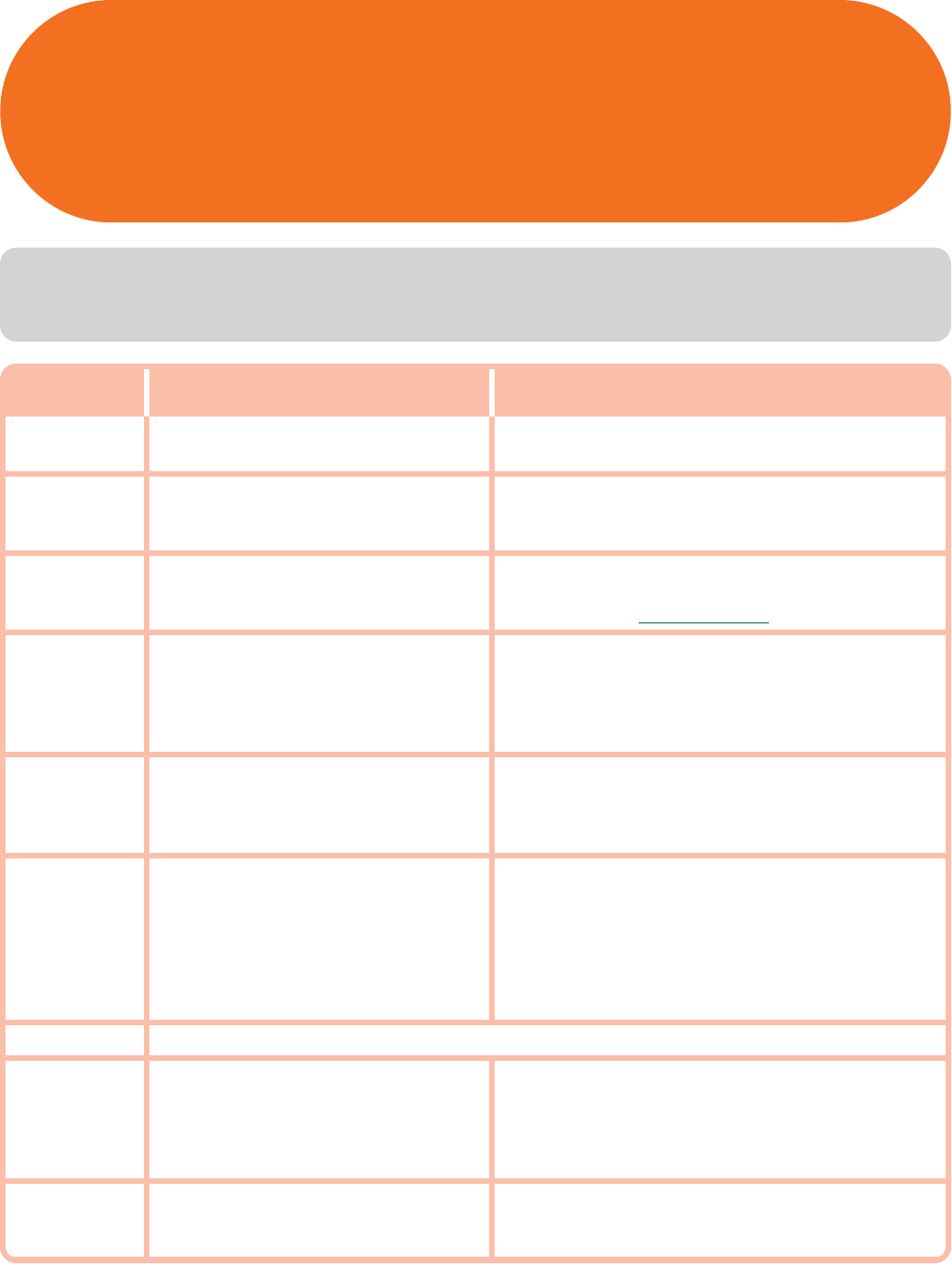

Time Activity Materials

5 minutes

As Girl Scouts Arrive:

Mental Health—What Comes to Mind?

• Paper

• Pencils or pens

10–15 minutes

Introduction to the Showing Up For Me

and You Patch Program for Seniors and

Ambassadors

• Markers

• Whiteboard or large piece of paper with an easel

10–15 minutes Activity 1: What Is Mental Health?

• Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions meeting aid

(one for each participant)

• Device to show Ending the Silence video

15 minutes Activity 2: Language Matters

• Your Language Matters meeting aid (one for

each participant)

• Recording devices, such as smartphones (optional)

• Pencils or pens

• Paper

10 minutes Stretch-and-Snack Break

• Nutritious snack items such as fresh fruit, trail mix,

granola bars, and water

• Paper plates and cups

• Disposable utensils

15 minutes Activity 3: Building Resilience

• Paper (enough for everyone)

• Pencils or pens

• Large construction paper (enough for everyone)

• Small sticky notes

• Markers

• Getting the Right Start meeting aid

(one for each participant)

5 minutes Stretch Break

15 minutes Activity 4: Supporting Others

• How to Help a Friend meeting aid (one for each

participant)

• Active Listening Checklist meeting aid (one for

each participant)

• Pencils or pens

5–10 minutes Reection and Wrap-up

• Suggestion box

• Paper

• Pencils or pens

Program at a Glance

*These suggested times total 90 to 105 minutes (1 ⁄ hour).

Please adjust as you see t for your group.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 10

● This Showing Up For Me and You Patch Program for Seniors and Ambassadors is designed to take 90 to 105 minutes

(1 ⁄ hours). Feel free to use another meeting to cover anything you don’t have time for.

● Start activities with the whole group before breaking out into smaller groups.

● You’ll nd suggested talking points under the heading “SAY.” Follow them as written or use them as a guide to share the

information in your own words.

Materials: Paper, pens

Purpose: Participants record their rst impressions of mental health.

Give everyone a piece of paper and have them write words or phrases they think of when they hear the term “mental health.” They

can write as much or as little as they want. Make sure they know there are no right or wrong answers. Have them fold their paper

and set it aside. They’ll look at it again at the ending reection period.

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

Notes to Facilitators:

As Girl Scouts Arrive: Mental Health—What Comes to Mind? (5 minutes)

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 11

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

Materials: Markers, whiteboard or large piece of paper with

an easel

Purpose: Participants start to learn about mental health and

mental wellness, do an icebreaker to see what experiences and

feelings they all have in common, and discuss how to create a

comfortable space for sharing.

SAY:

● Welcome to today’s Mental Wellness Patch Program for

Seniors and Ambassadors called “Showing Up For Me

and You.” I’m glad you’re here with me to explore mental

health and wellness.

● Please remember I am not a mental health professional.

There may be questions that I can’t answer or can only

answer with my own unique experience. Anything that

is left unanswered, I will work with our council to get

information and report back at a later date.

● What do you all think the difference is between mental

health and mental wellness? (Give time to respond.)

● Mental health is your emotional and psychological health.

Just like we all have a state of physical health, we all

have a state of mental health.

● We should be sensitive to how we deal with mental health

challenges because we might not know what other people

in the room are facing, which is okay! We are here to

discuss it, learn together, and support each other.

● If you have any discomfort about anything we talk about

or do, you can choose not to participate in the discussion

or activity and it’s perfectly ne.

● When you practice mental wellness, you do things to

support your mental health, like getting more sleep,

learning how to cope with stress, and nding ways to get

and give help when it’s needed.

● The goal is to give you tools to take care of yourself, ask

for help, and support others.

● And we’re going to get to all of that in just a bit. But rst,

has anyone played “Have You Ever?” (Give them time to

respond and describe the game they’ve played.)

● It’s a game where you’ll nd out more about each other by

responding to questions.

Have the group sit in a circle. Ask the following “Have you

ever…?” questions one at a time. Have group members

decide on a movement they’ll make to indicate that they’ve

done that thing or can relate to it. For example, they can

stand or raise their hand or nger. They can share the story

behind their responses if they want.

You’re encouraged to join the circle and respond along with

the rest of the group. You may nd it helpful to share a

couple of your own experiences to start the conversation or

keep it going.

Have you ever…?

● stopped being friends with someone because you

didn’t have the same interests any more

● felt left out of a group

● felt sad because someone you liked didn’t like you back

● gone outside or to your room to “blow off steam” when

feeling angry—OR—gotten mad and surprised yourself

with how angry you were

● asked for help with a personal problem

● had nights where it’s hard to sleep

● meditated

● written down thoughts to calm your mind

● felt pressured by a friend to do something you didn’t

want to do

SAY:

● What did you learn about yourself and each other?

(Give time to respond.)

● What did you notice that you had in common with each

other? (For example, maybe several have practiced

meditation or experienced sleepless nights.)

● Isn’t it amazing how common a lot of our experiences and

feelings are? But we don’t always realize that because we

may not feel comfortable talking openly about them.

● We want this to be a comfortable space where we can have

those conversations. Creating that kind of space, where

everyone feels able to participate and share, will make the

experience more meaningful and productive for all of us.

● How can we do that? Call out your suggestions and I’ll

write them down.

Introduction to the Showing Up For Me and You Patch Program

for Seniors and Ambassadors (10–15 minutes)

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 12

As the group comes up with their ideas, write them on a

whiteboard or large piece of paper on an easel that can be

kept in the meeting space where everyone can refer to it.

If needed, suggest the following:

● Use a signal when you want to share or add to the

conversation.

● Use “I” statements—focus on sharing your own

experience, not someone else’s.

● Encourage kindness and openness.

● Be respectful and sensitive when responding or

making statements.

● Keep the things you hear today condential. What’s

said here stays here.

● Think before you respond.

● Give everyone a chance to talk. Don’t talk over each

other.

● Make this a judgment-free zone. Everyone’s experience

is valid and important.

SAY:

● This is great! I’m going to keep this list up here at the

front of the room for us to refer to and keep in mind today.

● Like you, I’ll keep what I hear today condential.

However, if I hear certain things that should not be

kept secret because someone is at risk—for example, if

someone is harming themselves—I may need to consult

with a trusted adult to protect you.

● Now, let’s get started.

TIP: If at any point you nd the Seniors and Ambassadors

not respecting these norms, be sure to go back to this list.

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

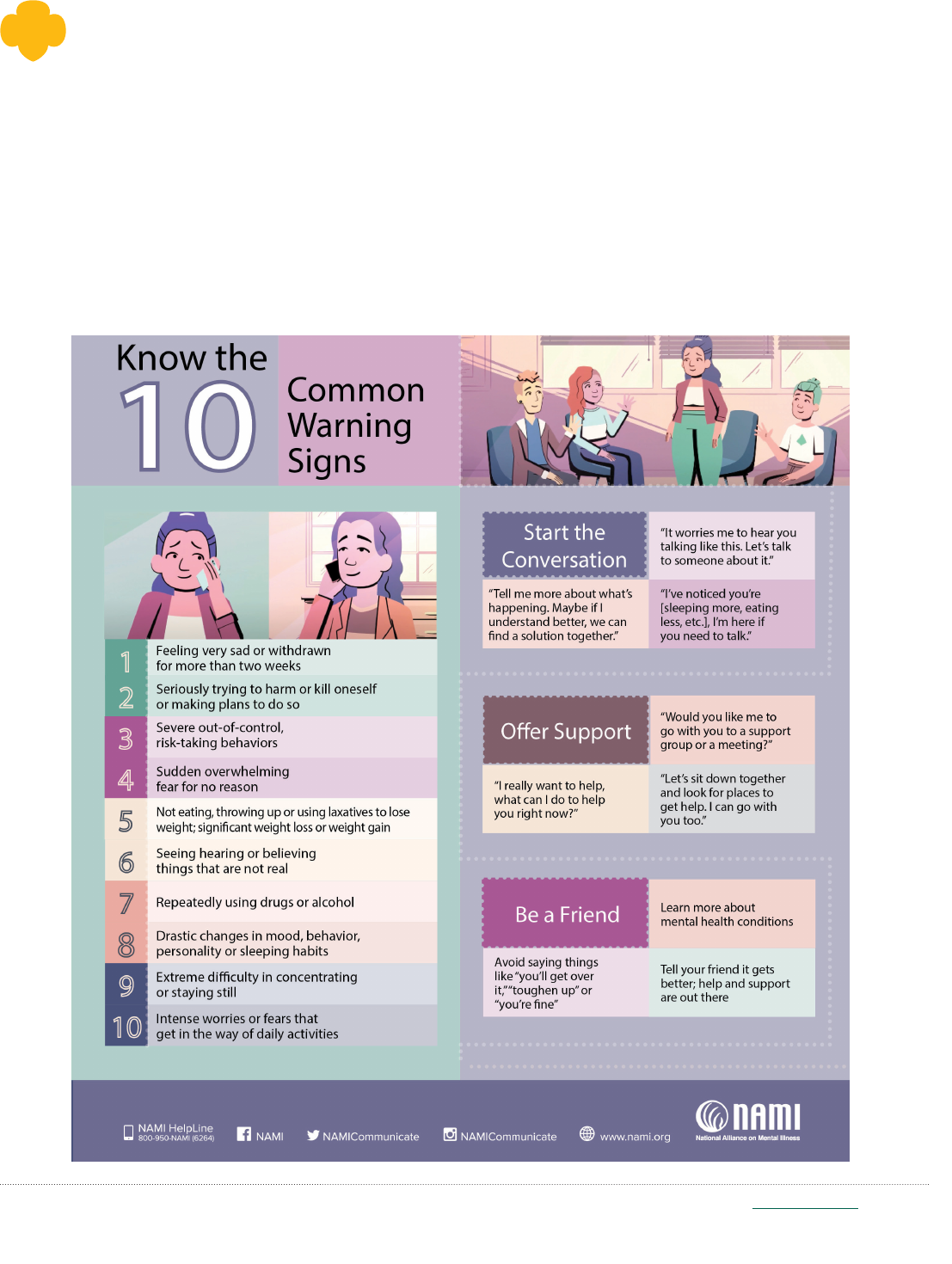

Activity 1: What Is Mental Health? (10–15 minutes)

Materials:

● Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions meeting aid

(one for each participant)

● Device to show Ending the Silence video

Purpose: Participants learn about mental health conditions

and explore warning signs and symptoms.

SAY:

● Call out some mental health conditions you’ve heard of.

(Give time to respond. If needed, offer examples such

as depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive

disorder, anxiety, ADHD, and schizophrenia.)

● What do you know about mental health conditions? (Give

time to respond. If needed, say that mental health

conditions affect how we think, feel, and act; they’re

common and treatable; they’re not anyone’s fault

or something to be ashamed of. If someone states

incorrect information, try to correct it in the moment,

or say that it’s not quite accurate and put it in the

parking lot to address later.)

● Now we’re going to look at some signs and symptoms of

mental health conditions.

● Before we do, it’s important to understand that while you

might recognize some of these in yourself, that doesn’t

necessarily mean you have a diagnosable mental health

condition. If you relate to any of the conditions we discuss

today, I strongly encourage you to share that with your

parent/caregiver or another trusted adult.

● First, let’s watch a short video called “Ending the Silence.”

It goes over the ten most common signs of a mental health

condition, and it was created by the National Alliance on

Mental Illness—NAMI for short.

Show the video. Afterward, have the group discuss

these questions:

● How do you feel about what you just saw?

● Were you already aware of any of these signs of a

mental health condition? Were there any that were

new to you?

● How would you respond if you saw any of these signs

in a friend or family member?

● How can we make it easier to talk about

mental health?

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 13

Pass out the Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions

meeting aid.

SAY:

● It’s not always easy to tell the difference between expected

behaviors and signs of a mental health condition.

● But there are common symptoms of mental health

conditions that we can look out for, like the ones on the list

I just gave you.

Give the group a few minutes to review on their own.

Tell them they can ask questions if they want to clarify

anything. Here are a couple of questions that might come

up, with suggested responses you can provide:

● How do you make these symptoms better or make

them go away? (Treatment, such as therapy and

doctor-prescribed medications, can help. Behavioral

changes—like getting more sleep and exercise, and

meditating—are important, too. Alternative treatments

like acupuncture and meditation can also ease the

symptoms. First, though, it’s helpful to start talking

about the symptoms—being alone with the experience

can be really painful.)

● Is there one condition on the list that’s worse or better

than another? (No. That’s because every mental health

condition affects people differently. Some people can

be diagnosed with just one condition, and some can

have three or four simultaneously. Symptoms can be

more severe or less severe. In many cases, other people

may not even realize that someone has a mental health

condition.)

SAY:

● As I said earlier, you might recognize some of these

symptoms in yourself or others at times, but that doesn’t

necessarily mean you or they have a mental health

condition.

● Maybe you’ve experienced these symptoms for a short

time when going through a stressful or tough situation.

Anyone want to share an example of that?

Let the group share if they can. If needed, offer these

examples:

● You might get headaches or have trouble sleeping

before a big test, but those symptoms tend to go away

after the stressful event is over.

● If you go through a major life change, like switching

schools or moving away from your closest friends, you

might feel sad and lonely at rst. These symptoms can

get better as time passes and you settle in, make new

friends, and get used to a new routine.

SAY:

● On the other hand, symptoms of a mental health condition

affect a person’s thinking, feeling, behavior, or mood.

These conditions deeply impact day-to-day living and

may also affect the ability to relate to others.

● A mental health condition isn’t the result of one event.

Research suggests multiple, linking causes. Genetics,

environment, and lifestyle can inuence whether someone

develops a mental health condition. A stressful job or

home life makes some people more susceptible, as do

traumatic life events.

● If you ever experience anything like that, it’s important

that you share it with your parents or caregivers, or

another trusted adult in your life.

● Talking about our mental health means that we’re more

able to get the support we need. But sometimes we’re not

comfortable talking about it. We’ll focus more on that in

the next activity.

● Take the Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions

meeting aid with you as a reminder and share what you

learned with your friends and family.

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 14

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

Activity 2: Language Matters (15 minutes)

Materials:

● Your Language Matters meeting aid

(one for each participant)

● Recording devices, such as smartphones (optional)

● Pencils or pens

● Paper

Purpose: Participants nd out about mental health stigma,

learn how the language they use to talk about mental health

makes a difference, and create a video to help ght stigma.

Pass out the Your Language Matters meeting aid.

SAY:

● In this next part, we’re going to look at language and

really zero in on how we can remove the stigma, or shame,

that so often surrounds mental health issues. This stigma

is what can make it difcult and uncomfortable to even

have discussions about mental health.

● The handout I just gave you is one I hope you’ll take home

and refer to often. It gives examples of language to use

and language to lose when talking about mental health.

Give the group a minute to read the meeting aid.

● Is there any language on the handout that you’ve used

yourself or heard someone use? What was it?

● Using language that encourages understanding is key to

breaking down the stigma associated with mental health.

● Have you heard that word before, “stigma”? What does it

mean? (Give time to respond. If needed, say that stigma

is a negative attitude about a person, group, condition,

or circumstance that’s thought to be different or “less

than.”)

● Why do you think that mental health conditions have a

stigma related to them? (Give time to respond.)

● There’s also something called self-stigma. That’s the

shame a person feels about some part of themselves.

● Many people who live with a mental health condition

have, at some point, been blamed for it. They’ve been

called names. Their symptoms have been referred to as

“a phase” or something they could control “if they only

tried.” All of these are examples of stigma, and the person

can internalize these messages as true.

● So how can we ght stigma? What ideas do you have and

why would they help?

Let the group lead this conversation. If needed, offer

these ideas:

● Talk openly about mental health.

● Learn more about mental health.

● Show compassion for those who have a mental

health condition or who are struggling with a

mental health challenge.

● Be conscious of language. Gently let anyone you’re

talking to know when the language they’re using is

harmful. You could tell them something like, “When

you say [example], that can be harmful to people with

mental health conditions. It’s more helpful to say

[example].”

SAY:

● These were all great ideas. Now you’re going to work in

small groups to write or lm a short video message about

ghting mental health stigma. Use the ideas you just

discussed or come up with new ones.

Divide the group into small teams to write a script for or

lm a short video message (if smartphones are available).

When they’re done, have them share their messages with

the group. If they wrote a script, have them read it out loud

or act it out.

SAY:

● Your video messages are excellent. How could you share

your message with more people?

● Before we continue, let’s recharge with a stretch-and-

snack break.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 15

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

Stretch-and-Snack Break (10 minutes)

Materials:

● Nutritious snack items such as fresh fruit, trail mix,

granola bars, and water

● Paper plates or cups

● Disposable utensils

Purpose: During a stretch-and-snack break, participants

explore how movement and nutrition can affect the way

they feel.

Encourage everyone to choose their own stretch and do it

for one or two minutes. They can do this standing or sitting,

whatever feels good to them. If they’re unable to think of

one, show them a couple of your favorites.

SAY:

● How did stretching make your body feel? (Give time to

answer.)

● How does movement affect how you feel mentally?

(Give time to answer.)

● Did you know that what you eat can also affect how you

feel? Let’s get a snack and talk about that some more.

Have the group select whatever snacks they’d like. While

they eat, talk with them about how nutrition impacts

mental health.

SAY:

● We’re taking a snack break to give our brains some

energy.

● Foods have nutrients that can help you stay alert and

strong, and make you feel better.

● Do you notice a difference in how you feel when you’re

hungry compared to when you’ve had a nutritious meal or

snack? (Give time to answer.)

● What foods and drinks do you think keep your body and

mind strong? (Give time to answer.)

● Hope you’re all feeling recharged! Let’s move on to the next

activity, where we’ll get into self-care and what it means

to be resilient.

Activity 3: Building Resilience (15 minutes)

Materials:

● Paper (enough for everyone)

● Pencils or pens

● Large construction paper (enough for everyone)

● Small sticky notes

● Markers

● Getting the Right Start meeting aid

Purpose: Participants explore different types of self-care,

identify stressful and positive things in their lives, talk

about why it’s important to get help, and learn about taking

care of themselves.

SAY:

● Did you know that one out of every six people ages 6 to 17

experiences a mental health condition each year? What do

you think of that statistic? (Give time to respond.)

● When someone is struggling, what should they do? (Give

time to respond; if needed, offer “get help” as an answer.)

● Let’s nd out more about what it takes to get help if you or

someone you know is struggling with something.

Pass out the Getting the Right Start meeting aid. Use this

next discussion to help familiarize participants with the

points made in the handout and lead into a discussion about

self-care and coping.

SAY:

● Why do you think it’s important to tell someone about a

mental health challenge?

● What points on this handout do you nd most helpful?

Or surprising?

● Why do you think it’s important not to wait to get help?

● What do you do when you’re having a tough day? How

do you move forward when you’re struggling with

something, like a difcult assignment at school?

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 16

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

● It’s okay to feel sad, hurt, or angry when you’re dealing

with a tough situation. Feeling our feelings—rather than

avoiding or trying to hide them—is a great way to process

them and take care of ourselves.

● One way to deal with tough situations is to practice

self-care. How do you dene that? What do you do for

self-care? (Give time to respond.)

● Your denitions are all great because self-care can mean

a lot of things.

● Taking a bath or writing in a journal are often our

go-to examples. But self-care can also mean:

• utilizing your support system

• giving yourself slack when you make a mistake or

fail at something

• saying no when something doesn’t feel good to you

• putting your phone down and taking a break from

connecting with others for a period of time

• advocating for yourself

• raising your voice to be heard

● Have you tried doing any of these? What was the situation

and how did it work out? (Give time to respond.)

● How do you think self-care is related to coping? (Give

time to respond. If you need to dene coping, it’s “the

things people do to help deal with stressful situations.”)

● What do you do to cope with tough situations? It may

be the same as what you do for self-care, or it may be

something different. (Give time to respond.)

● One example of a coping mechanism is to recognize the

things that stress you out and decide where or even if

they t into your life. That’s what you’re going to do now.

Ready?

Give everyone a piece of paper and have them make two

columns. In one column, they should list the things that

stress them out, such as a difcult relationship or an event

they’re not looking forward to. In the other column, they

should list the good stuff in their lives, such as a friendship

or an activity they love doing.

When they’re done with their lists, give everyone a piece of

construction paper and some sticky notes.

SAY:

● Draw a bubble in the middle of your paper.

● The inside of the bubble represents everything that feels

comfortable, enjoyable, and/or manageable for you. The

outside of the bubble represents everything that feels

uncomfortable, stressful, and/or difcult for you to manage.

● Write the items from your list on separate sticky notes—

one item per note.

● When you’re done, choose where to place each sticky note,

either inside or outside your bubble.

When everyone’s nished, give them the chance to share

and talk about their bubbles if they want. Whether they

share or not, everyone can discuss these questions:

● What are some ways you can open up a conversation

about a struggle you’re having? (If needed, offer these

ideas: Plan what you want to say; nd a private place

to talk; explain your challenge as clearly as you can;

come up with some next steps.)

● Why do you think it’s important to have these

conversations? (Answers could be: “So that it doesn’t

turn into a bigger issue down the line”; “The earlier you

speak up about something, the better chance you have

to manage the problem.”)

● What are the benets of being open or sharing with

someone when we’re struggling? (Answers could be:

“Having support makes it easier to deal with an issue”;

“You build a network of support—sharing with others

could make them more open to sharing with you when

they need help.”)

● Are you more likely to help someone else who is in

trouble than to help yourself? If so, why?

● Why did you make the placements you did?

● What do your placements say about what the items

mean to you or how you plan to deal with them in

your life?

SAY:

● Keep your bubble as a reminder of what you do and don’t

have room for in your life.

● Being aware of what things feel stressful and what you

can handle is one move toward taking care of yourself as

you navigate challenges. Remember you may not always

be able to avoid something that is causing stress.

● What does resilience mean to you? (Give time to answer;

if needed, share this denition: “Resilience is adapting

to or learning how to deal with life situations, such as

the ones you just identied. It’s a person’s ability to

bounce back after a setback, to learn from failure, and

to be willing to try again.”)

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 17

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

● Resilience is something we can all build to help us through

day-to-day difculties. It’s also important to remember

that there are some things that, no matter how resilient

you are, may still get you down—big things like racism,

gender discrimination, or climate disasters. If we feel

overwhelmed by these challenges, that’s okay. And if

someone else feels hurt by them, it doesn’t mean they

aren’t being resilient enough.

● What do you think are some traits of resilient people?

(If needed, offer that resilient people are exible and

resourceful, set realistic expectations for themselves,

and are willing to learn from and seek solutions

to difcult or unexpected situations. Examples of

resilient people: an athlete who recovers from an injury

by doing physical therapy; a person who experiences

travel delays but nds another way to reach their

destination; a law school graduate who fails the bar

exam but keeps trying and passes the third time.)

● You’re going to go through difcult experiences in life.

Maybe you’ll make decisions that turn out poorly. The

point is, you’re learning and growing from all of it. Or,

at minimum, you’re just getting through it. This builds

your resilience.

● What traits of resilience do you think you have and what

ones do you want to develop?

● Remember, being resilient doesn’t mean handling

everything alone. How is asking for support part of being

resilient?

● Why do you think failure can sometimes be okay?

● How do you think setting boundaries plays a role in being

resilient? (If needed, offer: “Boundaries are limits

people create to protect themselves from being hurt,

manipulated, taking on too much, or being taken

advantage of. A boundary looks like saying no to a

request from a friend, not checking email late at night,

or speaking up when a situation feels off.”)

● Setting boundaries isn’t always easy. It takes practice

to communicate how you feel. Have you ever had to

set boundaries with a friend or in a situation where

you weren’t comfortable? How did you do it? What, if

anything, would you have done differently?

Stretch Break (5 minutes)

Purpose: Give the group a short stretch/bio break.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 18

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

Activity 4: Supporting Others (15 minutes)

Materials:

● How to Help a Friend meeting aid

(one for each participant)

● Active Listening Checklist meeting aid

(one for each participant)

● Pencils or pens

● Paper

Purpose: Participants learn how to support a friend

or family member who’s struggling and practice active

listening.

SAY:

● Knowing how to use your voice and seek help is important

for your self-care and mental health. What would you

do if you shared your problem with someone who wasn’t

supportive or wasn’t able to help you? (Let the group

know this is a way to practice resilience: they can

nd support or seek advice from other resources or

identify others who might be able to help them. If they

need help with ideas, tell them they could try to nd

someone else in their family or community, look for

resources from a school counselor or faith leader, or

nd support in a crisis text line or hotline.)

● Knowing how to get help for yourself can also give you

skills to support a friend who is struggling.

● When you spend your time and energy helping someone

else, it can have a positive impact on your own self-

esteem.

● Maybe you can do something like that for a friend, too.

Have you ever had regular check-ins with friends just to

ask how they’re doing?

● Can you always tell when someone’s struggling with

something? (Give time to respond.)

● Probably not. If we open up and share how we are doing,

they might be more willing to share with us.

● It’s also important to know your limits and be realistic

about what support you can offer.

● You can be there for friends and family, but you might not

be able to help with a serious mental health condition.

What would you do if you were concerned with your

friend’s health or safety? (If needed, say: “Seek help

from a trusted adult or a trained professional.”)

Pass out the How to Help a Friend meeting aid. Tell the

group it gives tips on how to start the conversation, offer

support, and be a friend. Have the group take turns reading

each section out loud. Ask if anything they read feels

familiar or if they’ve experienced it themselves.

SAY:

● One important way to help a friend is by actively listening

to them.

● What does it mean to be an active listener? (Give time to

respond. If needed, say: “It means to focus on not only

the words someone is saying but also what’s being

communicated. It also means to reect and respond

thoughtfully.”)

● Do you know someone who is a good listener? What makes

them that for you? (Give time to respond.)

● As you’ve just pointed out, there are some skills to being

an active listener and you’ll practice them today.

Give everyone the Active Listening Checklist meeting aid

and have them read through the do’s and don’ts of being an

active listener.

Give each participant a pen and paper.

SAY:

● Write down a general issue you or someone you know is

dealing with on a piece of paper. It could be something like

stress about the future, a ght with a sibling, something

you read on social media, or a situation where you felt

left out. You don’t need to sign your paper—everyone will

remain anonymous.

● Hand me your paper when you’re done.

Fold the papers and place them in a bowl. (Read them

beforehand to make sure they’re general enough and will

work for this activity.)

Divide the group into teams of three. One team member will

be the Sharer, one will be the Listener, and one will be the

Observer. If you can’t form enough teams of three:

● For a two-person team, you or another facilitator/

volunteer can be the Observer.

● For a four-person team, two people can be Observers.

SAY:

● One of you will be the Sharer. You’ll share a tough

experience picked from a paper in the bowl.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 19

Facilitation Script and Activity Guide

● One of you will be the Listener. You’ll listen to the Sharer,

using techniques from the Active Listening Checklist.

Take a moment to review it again now if you’d like, before

your teammate starts sharing with you.

● And one of you will be the Observer. As the Sharer and

Listener do their thing, you’ll use the checklist to check

off the active listening traits that you see or hear. You can

also make notes on the checklist.

● Before you start, take a minute to decide which role each

of you wants to play.

Give the group ve to ten minutes for this activity. Give a

warning when there’s a minute left so they can wrap up.

Then get the group back together to discuss what they did

in their teams.

SAY:

● Sharers, what did you notice about the Listener? What

skills did they use that showed you they were actively

listening?

● Listeners, what were you able to pick up on from the

Sharer when you really listened to them?

● Observers, what active listening traits did you notice

most strongly? Are there any you didn’t check off? How

might they have helped in this situation?

● How do you all think active listening helped the person

who was sharing their problem? Did it help them nd a

solution or feel better?

● What do you think are the most important traits of active

listening?

● Do you think you need to have an answer to someone’s

problem to be supportive of them? (Answers could be:

“Sometimes just listening and caring is enough”; “It’s

important to let another person express themselves.”)

Note to facilitator: If the group wants to continue

practicing active listening, you can incorporate this activity

into a future troop meeting as time allows.

Reection and Wrap-up (5–10 minutes)

Materials:

● Suggestion box

● Pencils or pens

● Paper

Purpose: Participants reect on their impressions of

mental health when they arrive. They think about ways to

support their mental wellness.

Give the group time to respond to these reection questions:

● Look back at how you described mental health. Did

anything change? If so, what?

● What is something new you learned about mental

health and mental wellness?

● We covered a lot of topics today. What activity or

discussion did you nd most helpful or useful? Why?

● What immediate changes will you make to support

your own mental health and help others? (Answers

might be: “Talk to a trusted adult”; “Practice self-care”;

“Be more aware of my friend’s emotions”; or “Know

when and how to seek help if I need it.”)

SAY:

● Before you go, let’s do a quick, calming breathing exercise.

Mindful breathing is something you can do anytime,

anywhere to calm yourself or a friend, or to cope with a

stressful situation. Let’s do one type of mindful breathing

called a “box breath.”

Have participants:

1. Inhale through their noses for four seconds

2. Hold their breath for four seconds

3. Exhale slowly through their mouth for four seconds

4. Pause quietly for four seconds

Do this for a few rounds.

(Tip: You can trace the shape of a box in the air with your

nger while you count, to help visualize the four steps of

the breath.)

SAY:

● Do you think you’ll try mindful breathing the next time

you feel worried or stressed? It’s a great self-care practice!

● I am so glad you joined me today. Thank you for sharing

and being respectful!

Before the group leaves, let them know what the suggestion

box is and how to use it. Have them put anonymous

feedback, questions, or comments into the box.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 20

We recommend the following additional steps to keep lines of communication open with parents/caregivers and to continue

integrating mental wellness into Girl Scout activities:

● Send a follow-up email to parents and caregivers. Share what their Seniors and Ambassadors did and learned about

mental wellness. See the Customizable Post-Event Email to Parents/Caregivers (p. 22).

● Send a follow-up email to your council to let them know how your Showing Up For Me and You Patch Program went. If

your council has prepared a survey for you to ll out, send that in.

● Incorporate mental wellness moments in future troop meetings. Check out GSUSA’s Resilient. Ready. Strong. patch program

for some ideas, such as playing music or creating a “happy box” with things that make Seniors and Ambassadors

smile. You can also ask them to choose or vote on what kind of wellness activities they’d like to do to start or end each

meeting. It might be a breathing exercise, a yoga move, or a moment of silence to think about what they’re grateful for.

● For Seniors and Ambassadors who are college bound or thinking about college, suggest that they take a look at the

NAMI guide Starting the Conversation: College and Your Mental Health, written for both students and parents/

caregivers. College can be emotionally challenging, and they can prioritize their mental health by looking for on-

campus support, social connections, and ways to connect with their new community before they start.

Next Steps

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 21

Customizable Invitation Email to Parents/Caregivers

Next Steps

Use this email template to help you reach out to Seniors and Ambassadors and their families or caregivers in

advance of conducting the Showing Up For Me and You patch program. This is the suggested language for inviting

participants. Customize as needed.

Dear Girl Scout Families and Caregivers,

Seniors and Ambassadors are invited to take part in a 90-minute Mental Wellness Patch Program called Showing Up For

Me and You on [DATE]. Girl Scouts of the USA collaborated with experts at the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) to

develop the program, and also received input from other mental health professionals and Girl Scout council leaders. It has

been generously funded by the HCA Healthcare Foundation.

Girl Scouts will participate in activities and have discussions about ghting mental health stigma, dealing with stressful

situations, building resilience in the face of challenges, and supporting friends who are struggling. This will be a supportive

space to learn about mental wellness.

[Note to facilitator: If your meeting is in a location different from your regular troop meetings, provide the address and

directions.]

If you have any questions, please contact me or the council directly. I look forward to seeing your Girl Scout on [DATE].

Thank you for supporting Girl Scouts.

Best regards,

[YOUR NAME]

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 22

Customizable Post-Event Email to Parents/Caregivers

Next Steps

Use this email template to help you send a follow-up email to parents and caregivers. Share what their Seniors and

Ambassadors did and learned about mental wellness. This is suggested language for a post-event communication

to parents and caregivers. Customize as needed.

Dear Girl Scout Families and Caregivers,

Today, your Girl Scouts participated in the Mental Wellness Patch Program for Seniors and Ambassadors: Showing Up For

Me and You. They came up with strategies to ght mental health stigma, learned how to cope with tough situations in their

lives, and practiced active listening to support friends who are struggling.

[Note to facilitator: Include any additional information you’d like about how the program went, the positive outcomes you

observed, and/or your plans to incorporate mental wellness moments into future meetings.]

If you have any questions, please contact me or the council directly. Thank you for supporting Girl Scouts.

Best regards,

[YOUR NAME]

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America (GSUSA). All rights reserved. Not for commercial use. This material

is proprietary to GSUSA and may be used, reproduced, and distributed exclusively by GSUSA staff, councils, Girl Scout

volunteers, service units, and/or troops solely in connection with Girl Scouting.

Showing Up For Me and You Facilitator Guide | 23

Meeting Aids

Use these meeting aids to facilitate this program.

For Facilitators:

● For Facilitators: Mental Health Terms to Know

● For Facilitators: Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions

● For Facilitators: What to Know About Identity, Culture, and Mental Health

● For Facilitators: Girl Scout Safety Activity Checkpoints—Overall Health, Well-Being, and Inclusivity

For Seniors and Ambassadors:

● For Seniors and Ambassadors: Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions

● For Seniors and Ambassadors: Your Language Matters

● For Seniors and Ambassadors: Getting the Right Start

● For Seniors and Ambassadors: How to Help a Friend

● For Seniors and Ambassadors: Active Listening Checklist

Anxiety Disorders: A group of related conditions, each having unique symptoms. However, all anxiety

disorders have one thing in common: persistent, excessive fear or worry in situations that are not

threatening. Everyone can experience anxiety, but when symptoms are overwhelming and constant—often

impacting daily living—it may be an anxiety disorder.

Attention Decit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A developmental disorder dened by inattention

(trouble staying on task, listening), disorganization (losing materials), and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity

(dgeting, difculty staying seated or waiting). While ADHD occurs among people of all identities, it is

generally underdiagnosed in girls.

Bipolar Disorder: Causes dramatic shifts in a person’s mood, energy, and ability to think clearly.

Individuals with this disorder experience extreme high and low moods, known as mania and depression.

Some people can be symptom-free for many years between episodes.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): A condition characterized by difculties regulating emotion.

This means that people who experience BPD feel emotions intensely and for extended periods of time;

it’s harder for them to return to a stable baseline after an emotionally triggering event. This difculty can

lead to impulsivity, poor self-image, stormy relationships, and intense emotional responses to stressors.

Struggling with self-regulation can also result in dangerous behaviors such as self-harm (e.g., cutting).

Clinical Social Workers: Practitioners trained to evaluate a person’s mental health and use therapeutic

techniques based on specic training programs. They’re also trained in case management and

advocacy services.

Counselors, Clinicians, Therapists: Masters-level healthcare professionals trained to evaluate a person’s

mental health and use therapeutic techniques based on specic training programs. They operate under a

variety of job titles—including counselor, clinician, therapist, or something else—based on the

treatment setting.

Depression: Involves recurrent periods of clear-cut changes in mood, thought processes, and motivation

lasting for a minimum of two weeks. Changes in thought processes typically include negative thoughts and

hopelessness. Depression can also affect sleep/energy, appetite, and weight.

Eating Disorders: A group of related conditions involving a preoccupation with food and body weight

that cause serious emotional and physical problems. Each condition involves extreme food and weight

issues; however, each has unique symptoms that separate it from the others. Common eating disorders are

anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder.

Mental Health Terms To Know

Conversations about mental health and mental wellness are central to the Girl Scout Junior Knowing My

Emotions, Cadette Finding My Voice, and Senior & Ambassador Showing Up For Me and You patch programs.

Before leading any discussion on mental health and mental wellness, familiarize yourself with these

denitions of mental health terms that may come up. Doing so will help you to lead a lively, productive, and

informed conversation among troop members. This glossary from the experts at the National Alliance on

Mental Illness (NAMI) provides denitions for mental health terms that may come up.

This glossary from the experts at the National Alliance on Mental Illness provides denitions for mental

health terms that may come up.

24

Adult Facilitators | Knowing My Emotions, Finding My Voice,

Showing Up For Me and You

Detailed choice activities, meeting tools, and additional resources and materials can be found within the Volunteer Toolkit on my.girlscouts.org.

Made possible by HCA Healthcare Foundation

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America. All rights reserved.

Mental Health Terms to Know

Mental Illness: A condition that affects a person’s thinking, feeling, or mood. These conditions may affect

someone’s ability to relate to others and function day to day. Each person will have different experiences,

even people with the same diagnosis.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD): Characterized by repetitive, unwanted, intrusive thoughts

(obsessions) and irrational, excessive urges to do certain actions (compulsions). Although people with

OCD may know that their thoughts and behavior don’t make sense, they are often unable to stop them.

Symptoms typically begin during childhood, the teenage years, or young adulthood.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Traumatic events—such as an accident, assault, military

combat, or a natural disaster—can have lasting effects on a person’s mental health. PTSD can occur at any

age. Symptoms, which include reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal, usually begin within three months

after experiencing or being exposed to a traumatic event. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, or substance

use often accompany PTSD.

Psychiatrists: Licensed medical doctors who have completed psychiatric training. They can diagnose

mental health conditions, prescribe and monitor medications, and provide therapy. Some have completed

additional training in child and adolescent mental health, substance use disorders, or geriatric psychiatry.

Psychologists: Practitioners who hold a doctoral degree in clinical psychology or another specialty such

as counseling or education. They are trained to evaluate a person’s mental health using clinical interviews,

psychological evaluations, and testing. They can make diagnoses and provide individual and group

therapy.

Self-harm: Also called self-injury, this is when a person hurts themselves on purpose. One common

method is cutting the skin with a sharp object, but anytime someone deliberately hurts themselves, it is

classied as self-harm. Some people feel an impulse to cause burns, pull out hair, or pick at wounds to

prevent healing. Extreme injuries can result in broken bones.

25

Adult Facilitators | Knowing My Emotions, Finding My Voice,

Showing Up For Me and You

Detailed choice activities, meeting tools, and additional resources and materials can be found within the Volunteer Toolkit on my.girlscouts.org.

Made possible by HCA Healthcare Foundation

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America. All rights reserved.

Mental Health Terms to Know

26

Detailed choice activities, meeting tools, and additional resources and materials can be found within the Volunteer Toolkit on my.girlscouts.org.

Made possible by HCA Healthcare Foundation

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America. All rights reserved.

Adult Facilitators | Knowing My Emotions, Finding My Voice,

Showing Up For Me and You

It’s important for adult leaders of Girl Scouts to know and understand the symptoms of mental health conditions;

however, noticing any of these symptoms in yourself or someone else doesn’t necessarily mean a diagnosable

mental health condition is present. Refer to the meeting aid “Girl Scout Safety Activity Checkpoints—Overall

Health, Well-Being, and Inclusivity” for further guidance on addressing and reporting mental health concerns

about a Girl Scout.

Symptoms of Mental

Health Conditions

Conversations about mental health and mental wellness are central to the Girl Scout Junior Knowing My

Emotions, Cadette Finding My Voice, and Senior & Ambassador Showing Up For Me and You patch programs.

Before leading any discussion on mental health and mental wellness, familiarize yourself with the signs and

symptoms of mental health conditions. Doing so will help you to lead a lively and productive conversation

among troop members. This tip sheet explains ve of the most common mental health conditions that may

come up in your discussions with troop members.

Anxiety:

Gets upset when not on time for things like homeroom, practices, and parties; needs the comfort

of a schedule and reacts negatively when plans change; seeks perfection in grades, extracurriculars,

or cleanliness.

Attention Decit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD):

Has difculty paying attention and listening when spoken to; is hyper focused on things they enjoy; moves

constantly; talks excessively and over people; jumps from subject to subject; loses things a lot; starts many

tasks but has a hard time nishing them; is forgetful; has sensory sensitivities.

Depression:

Stops participating in things they used to enjoy; is not responsive to texts and invites; is easily frustrated,

irritated, or short-tempered; could also be overachieving or taking on too much.

Eating Disorders:

Eats too little or too much; has an intense fear of gaining weight; engages in excessive exercise;

worries over calorie intake.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD):

Avoids situations that make them recall the traumatic event; experiences nightmares or ashbacks about

the trauma; plays in a way that repeats or recalls the trauma; acts impulsively or aggressively; frequently

feels nervous or anxious; experiences emotional numbness; has trouble focusing at school

Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions

27

Adult Facilitators | Knowing My Emotions, Finding My Voice,

Showing Up For Me and You

Detailed choice activities, meeting tools, and additional resources and materials can be found within the Volunteer Toolkit on my.girlscouts.org.

Made possible by HCA Healthcare Foundation

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America. All rights reserved.

What to Know About Identity, Culture, and Mental

What to Know About Identity,

Culture, and Mental Health

Girl Scouts have a range of identities and come from a range of cultures. The following information, adapted

from the experts at the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), will help you understand how identity and

cultural background can affect someone’s responses to mental health issues and access to treatment. Each

of the communities below consists of sub-communities with diverse cultures and identities. It’s important to

recognize and respect the uniqueness of each. Mental health needs and experiences vary among subgroups.

Asian American and Pacic Islander (AAPI) Community

This racial identity is inclusive of 50 distinct ethnic groups speaking more than 100 languages, with

connections to Chinese, Indian, Japanese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, Hawaiian, and other Asian and

Pacific Islander ancestries.

It’s a common cultural experience for members of the AAPI community to experience a deep sense of

community and strong family bonds, which can help them build resilience to deal with challenges.

Many second-generation members of the AAPI community struggle to nd balance between traditional

cultural values and the pressure to assimilate into the norms of mainstream (white) American society.

Barriers to addressing mental health issues include:

•

Language, especially when seeking counseling for sensitive or personal issues.

•

Fear of jeopardizing immigration status or citizenship.

•

Stigma and shame (don’t want others to have a negative opinion of them).

•

The “model minority” myth: a misleading belief that Asian Americans and Pacic Islanders are

uniformly well adjusted, hard-working, and well educated, and enjoy more socioeconomic success

than other people of color. This stereotype can result in others not attending to challenges expressed

by members of the AAPI community.

28

Adult Facilitators | Knowing My Emotions, Finding My Voice,

Showing Up For Me and You

Detailed choice activities, meeting tools, and additional resources and materials can be found within the Volunteer Toolkit on my.girlscouts.org.

Made possible by HCA Healthcare Foundation

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America. All rights reserved.

What to Know About Identity, Culture, and Mental

Black/African American Community

This racial identity is inclusive of ethnic groups who can trace their origins in total or in part to the continent

of Africa. The experience of being Black in America varies widely, but shared cultural factors play a role in

mental health.

Experiencing racism, discrimination, and inequity can signicantly affect a person’s mental health.

Being treated or perceived as “less than” because of skin color can be stressful and even traumatizing.

Black adults in the U.S. are more likely than white adults to report persistent symptoms of emotional

distress, such as sadness, hopelessness, and feeling like everything is an effort.

Barriers to addressing mental health issues include:

•

Inhibited geographic access to quality mental health care due to racial segregation and

inequitable distribution of resources.

•

Socioeconomic factors that limit access to treatment options.

•

Internalized stigma: the perception, especially among older Black adults, of mental health conditions

as personal weaknesses.

•

Mistrust of healthcare providers due to bias and lack of cultural understanding.

•

Preference to seek support from faith communities.

Hispanic / Latinx Community

In the U.S., this community includes people from many different nations and regions of the world: Mexico,

Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central America, and South America, among others. While largely regarded as one

community, it’s comprised of various racial and ethnic groups.

Hispanic/Latinx communities are just as vulnerable to mental illness as other racial and ethnic groups,

but, due to structural and institutional barriers, they don’t have equal access to quality treatment. More

than half of Hispanic/Latinx people aged 18–25 with serious mental illness may not receive treatment.

Barriers to addressing mental health issues include:

•

Language, especially when seeking counseling for sensitive or personal issues.

•

Lack of health insurance coverage.

•

Socioeconomic factors and cost of healthcare services.

•

Fear of jeopardizing immigration status or citizenship.

•

Mistrust of healthcare providers due to bias and lack of cultural understanding.

•

Stigma and shame: This community fears being labeled “crazy” and doesn’t want to bring

shame to their family. They prefer to keep challenges at home private.

29

Adult Facilitators | Knowing My Emotions, Finding My Voice,

Showing Up For Me and You

Detailed choice activities, meeting tools, and additional resources and materials can be found within the Volunteer Toolkit on my.girlscouts.org.

Made possible by HCA Healthcare Foundation

© 2023 Girl Scouts of the United States of America. All rights reserved.

What to Know About Identity, Culture, and Mental

Indigenous / Native Community

Indigenous/Native people are those who have been living on this land prior to European colonization. There are 574

federally recognized tribal nations in the U.S., as well as tribes living without official recognition. These nations include

over 200 Indigenous languages (and many dialects within those languages) and countless diverse cultures, traditions,

and histories.

The traumatic history of extermination, displacement, and forced assimilation of Indigenous/Native peoples

continues through economic and political marginalization, discrimination, and inadequate access

to education, healthcare, and social services.

The multigenerational trauma that Indigenous/Native people have endured can lead to mental illness,

substance use disorders, and suicide.

Suicide rates for Indigenous/Native adolescents are more than double the rate for White adolescents.

Barriers to addressing mental health issues include:

•

Language, especially when seeking counseling for sensitive or personal issues.

•

Indian Health Services (IHS) is underfunded and unable to offer services to meet mental health

needs of the community.

•

Community members tend to live in rural and isolated locations with high rates of poverty

and unemployment.

•